I really enjoy receiving AdaBoxes. They are fun little surprise example projects to build using hardware I might not have thought to get on my own. After completion, they often go into my drawer of available microcontrollers. I’ve found it great to have spare microcontrollers around because when the idea for a project bites me, I can jump on it immediately with full momentum, versus having to wait for the parts to arrive in a week.

AdaBox 011 was something called a PyPortal. This is a little IoT device with WiFi and a screen. It’s programmed in Python, which makes it extremely accessible, but the whole concept of running Python on an embedded system makes the old-school embedded engineer in me cringe.

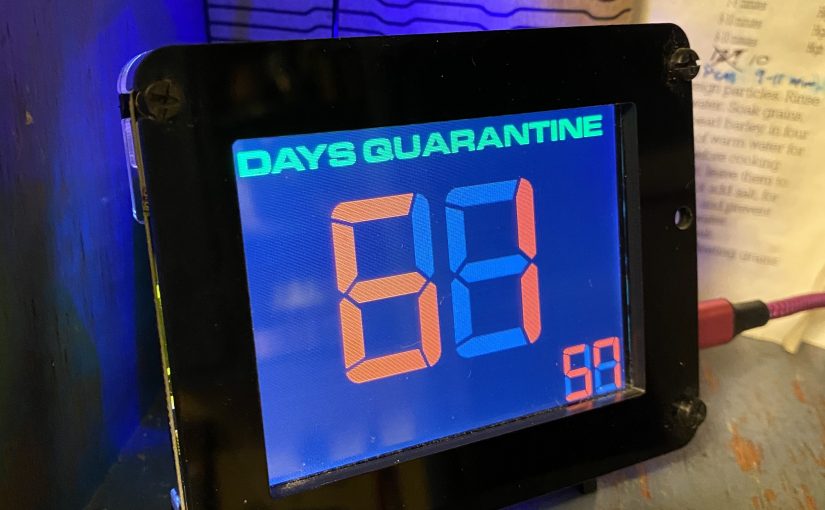

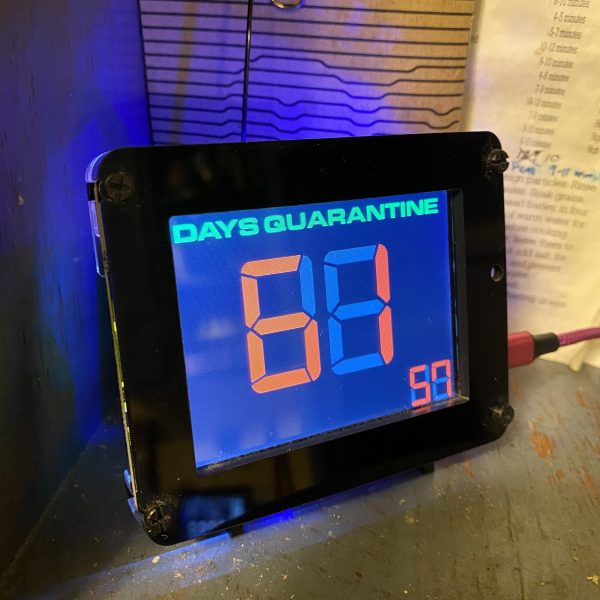

We’ve been keeping a paper quarantine calendar to mark the days and remember the highlights. I thought back to the PyPortal, and decided that building out a quarantine day counter would make a good project to get used to the CircuitPython dialect of Python.

The code itself is fairly simple. It connects to the internet to grab the current date/time, since the device does not have its own realtime clock. It uses the Python date library to calculate the elapsed number of days. It then updates the screen with some skeuomorphic LED digit graphics.

As you may notice, there are two sets of counters. That’s because we somewhat broke quarantine four days in. This was two weeks before Oregon’s official stay-at-home order, but I went through with an appointment with my hair stylist — masked while traveling, but unmasked at the salon (which was fairly empty). Christine went to write at Starbucks for a bit (in a mask, keeping distant from other customers). I don’t think the importance of self-isolating had fully hit us yet.

Getting the code running was a little bit aggravating. While I know Python itself very well, the CircuitPython libraries aren’t very well documented. There are lots of simple examples, but going beyond those was difficult. Getting things to appear on screen isn’t as simple as poking bytes into a framebuffer. You have to go through several layers of abstraction, each with its own set of limitations. I’d definitely recommend CircuitPython as a good starter language for simple microcontroller projects (LEDs, reading pins, and the like), but adding a screen adds some opaque complexity, which I’m not sure I could recommend to a beginner, unless they had a project that doesn’t deviate far from one of the example projects. And for me, personally? I was really pining to be able to do everything in C.

The code and graphic assets live on GitHub, if you’d like to make one for yourself. Just poke in your start date into the constants. Comment out the smaller counter if it doesn’t suit you.