Overview

Grep is a tool for Unix-like operating systems that performs searching within files. It’s also a great tool for many word puzzles. If you are on OS X or Linux, you already have it. On Windows, you’ll need a Unix-like subsystem such as Cygwin.

At the highest level, grep takes two things and then shows you the results:

- the thing to search for – In the simplest case, this is a chunk of a word. In more advanced searches, this can be a complex set of match rules.

- the thing to search through – A dictionary file of some sort.

Every Unix-like operating system has a dictionary file located at /usr/share/dict/words. The examples I will present here will use that dictionary, but be aware that the dictionary isn’t the same across different variants of Linux/Unix. You will want to find a dictionary that works best for you. The Scrabble dictionary is a good candidate, but remember that it is (intentionally) missing proper nouns. The Nutrimatic dictionary is extensive, as it is the result of scanning Wikipedia for the most common words, so you may want to trim it down a bit. For more on the topic of dictionary files, take a look at my blog post “Dictionary files: are they all created equal?”.

Note for programmers: I’ve intentionally simplified the examples here into a cookbook of grep examples. I do not get into the details of certain commands, for example the “.*” wildcard. This article is not a primer in regular expressions, but simple grep recipes to follow.

Syntax

The grep command that we will use looks like this:

grep {options} {thing to search for} {file to search through}

More specifically, it will look like this:

grep -i {thing to search for} /usr/share/dict/words

The “-i” means “ignore case.” It says that capital letters do not matter. Searching for “cal” will match both calorie and California with “-i” given. Without it, “cal” matches calorie but not California and searching for “Cal” matches California but not calorie. Because upper- and lowercase generally do not matter in puzzles, we’ll always use the “-i” flag.

The “thing to search for” term will consist of letters, but may also have some special symbols to indicate more advanced search methods.

Simple searches

Let’s start with a simple search. We want to find every word that matches “maze” in any way:

grep -i maze /usr/share/dict/words

This gives us, of course, “maze.” It also gives things like amaze, amazement, mazelike, mazer, unamazed, and (in my dictionary) schlimazel.

Try it with “plus” and you’ll get stuff like plush and surplus.

With “plex” you might get results like Plexiglass, simplex, complex, cataplexy, and perplex.

The simple searches are fairly straightforward, and you get a lot of what you expect.

Pinning the front or back

There are two special symbols that “pin” your match to the front of a word, the back of a word, or both.

Start your search term with the carat (^) to pin the front of the word:

grep -i ^unic /usr/share/dict/words

This will return results such as unicorn, unicycle, UNICEF, unicolored, and unicelled.

To constrain your search to the end of a word, end your search term with a dollar sign:

grep -i cycle$ /usr/share/dict/words

This gives you things like unicycle, bicycle, motorcycle, biocycle, endocycle, hemicycle, microcycle, and recycle.

Constraining both the front and back may seem weird now, but it is possible. Without other special symbols in the middle, it simply tells you whether or not the word exists in the dictionary file:

grep -i ^monocycle$ /usr/share/dict/words

This word exists in my dictionary file, so one match was returned. If you search for a nonexistent word, nothing is returned.

Wildcards

There are two types of wildcards we will discuss here. The first is a “match exactly one letter” wildcard. The other is “match any letters.” Wildcards are typically where you would use the pin-front and pin-back symbols.

Let’s look at a simple case. You want a 4-letter word that begins with “m” and ends with “s”. The grep command for that looks like this:

grep -i ^m..s$ /usr/share/dict/words

You will get results like Mars, maps, Macs, miss, mens, moms, moss, and muss.

You can get a list of every 4-letter word in the dictionary file with this command:

grep -i ^....$ /usr/share/dict/words

If you have a crossword clue with a few known letters, you can replace the dots with known letters:

grep -i ^e.c....p....$ /usr/share/dict/words

Knowing just those three letters narrows down the results to encyclopedia and encyclopedic.

The other kind of wildcard is for cases where you don’t care about an exact length. You want to match any number of letters. This is specified with a dot-star, or more specifically the “.*” pair. If you wanted to find a word of any length that started with the letters “con” and ended with the letters “red” you’d run:

grep -i '^con.*red$' /usr/share/dict/words

Notice that I wrapped my search term in single-quotes. Most Unix shells do not like the asterisk symbol and will attempt to do stuff with it before passing it to grep, ruining your grep command. To tell the Unix shell to treat the asterisk as a literal asterisk, you have to wrap the search term in single-quotes.

This command gives you results such as conferred, configured, conjectured, conquered, considered, conspired, and contoured.

Selecting from a collection of letters

As you learned above, the dot wildcard matches any letter. But what if you don’t want it to match any letter? What if you wanted it to match one of several possible letters. For example, let’s say you wanted “.” to represent a vowel. Or let’s say you wanted to find all possible matches for a crossword clue and you were unsure of one of the intersecting words – it could be one of two things, which makes the intersecting letter one of two possibilities.

Let’s look at the vowel case. We might want to find a four letter word that start with “s” and has two vowels in the middle. The command looks like this:

grep -i '^s[aeiou][aeiou].$' /usr/share/dict/words

Note that brackets are special characters like asterisks, requiring us to wrap our search term in single-quotes.

This matches soil, soar, soap, seem, seer, sees, seas, and may even match (if your dictionary includes proper nouns) SAAB and Suez.

In the crossword case, let’s say you needed a 7-letter word. You know for sure that it starts with “el”. The basic command looks like this:

grep -i ^el.....$ /usr/share/dict/words

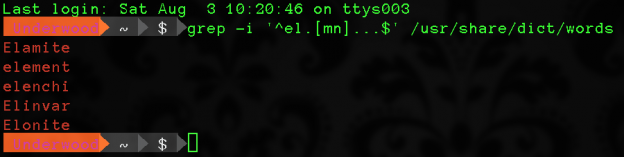

This returns about 200 words in my dictionary, which might be a lot to sort through. Let’s say that you thought the fourth letter was either an “m” or an “n” due to the word intersecting at that position. The revised command then looks like this:

grep -i '^el.[mn]...$' /usr/share/dict/words

Basically, you take out the dot and replace it with “[mn]” (and wrap the whole thing in single-quotes because you introduced the brackets).

Basically, you take out the dot and replace it with “[mn]” (and wrap the whole thing in single-quotes because you introduced the brackets).

This returns, on my system, 16 words. They’re all unusual and/or proper nouns except for element, which seems like a likely candidate.

Going further

There are much more advanced things you can do with grep search expressions. They are technically called “regular expressions” and a Google search for that term can lead you to all the other interesting possible commands.

In designing puzzles, I’ve used grep in several ways:

- Finding a good word to fit in a crossword-like array of intersecting words.

- Finding chains of words where the first few letters overlap, for instance:

EDITABLE

LEBANESE

SEVERELY

LYRICIST

STEADMAN

ANIMATED

EDITABLE

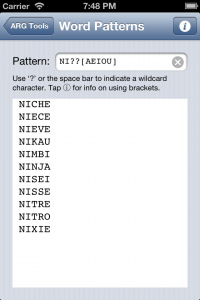

A subset of this functionality is available in the “Word Patterns” area of ARG Tools. Instead of using dots to match any letter, ARG Tools uses a much more visible question mark. Brackets work exactly the same as described in this article. The text you enter in ARG Tools has an implied “^” at the front and “$” at the end. It only looks for exact matches, as it is intended to be a more crossword-like word search tool.

A subset of this functionality is available in the “Word Patterns” area of ARG Tools. Instead of using dots to match any letter, ARG Tools uses a much more visible question mark. Brackets work exactly the same as described in this article. The text you enter in ARG Tools has an implied “^” at the front and “$” at the end. It only looks for exact matches, as it is intended to be a more crossword-like word search tool.